The motion of no confidence submitted by the uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) Party against President Cyril Ramaphosa is currently undergoing internal parliamentary scrutiny before it can be formally tabled. The delay follows the party’s resubmission of its motion to ensure it aligns with the procedural requirements set by the legislature.

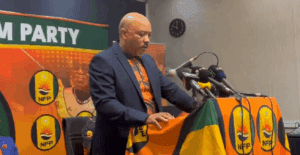

This resubmission became public knowledge after MK Party chief, Colleen Makhubele, raised the matter during a meeting of the National Assembly Programme Committee. In her query, she pointed to the absence of the motion from Parliament’s current agenda.

“We submitted a motion of no confidence. We would like to know when it will be tabled and how far it is,”

Makhubele asked.

“I know there are amendments that were submitted. I do not see it in the programme or anywhere in the agenda,”

she added.

Despite the motion’s initial submission last month, it was returned for adjustments to meet technical and legal standards. Masibulele Xaso, Secretary to the National Assembly, confirmed that the revised version had been received and is under final assessment.

“We have gone through it technically. We are finalising that. The advice will be presented to the Speaker and once the Speaker has considered the matter, the party will be responded to,”

said Xaso.

Speaker of the National Assembly, Thoko Didiza, provided additional context to Makhubele, emphasising that the motion had not been included in the formal programme as the parliamentary leadership had yet to respond to the resubmission.

“We did not raise it on the programme because we needed to respond to the party first after you resubmitted and then thereafter it will be duly dealt with. I hope you would understand that,”

Didiza told Makhubele.

To which Makhubele replied,

“Thank you Speaker, well noted.”

The MK Party originally introduced the motion in July, shortly after controversial claims emerged from KwaZulu-Natal Police Commissioner, Lieutenant-General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi. Mkhwanazi had made allegations implicating Police Minister Senzo Mchunu, prompting political backlash and renewed scrutiny over executive accountability.

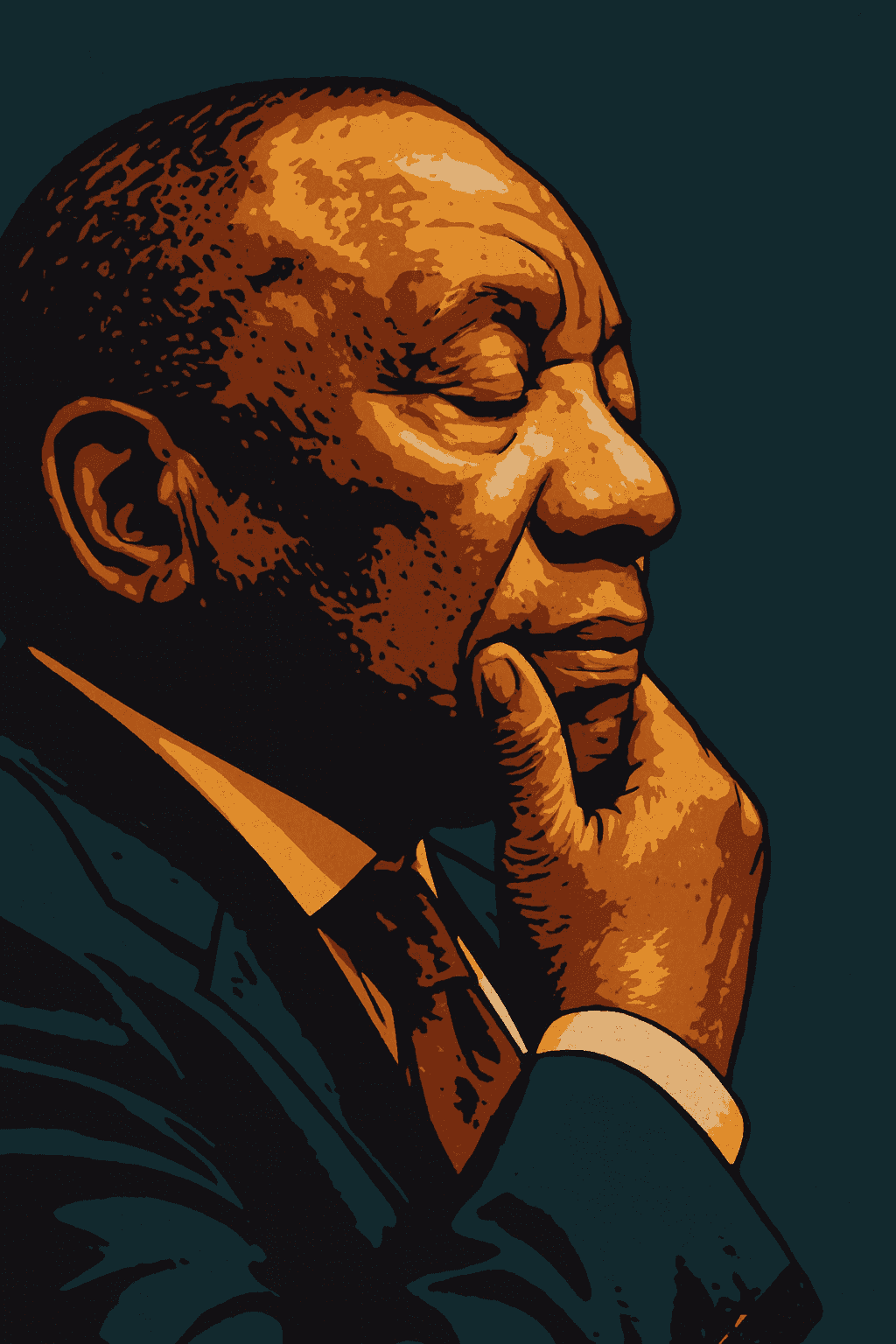

In a press briefing held on July 22, Makhubele outlined the party’s rationale for targeting President Ramaphosa, saying his failure to act decisively against Minister Mchunu and to protect South Africa’s vulnerable communities represented a betrayal of public trust.

“We put the motion of no confidence on Ramaphosa for his failures, chief among them, failure to fire Mchunu and to protect the most vulnerable in society,”

Makhubele said.

Complicating matters further, the MK Party recently suffered a legal defeat in the Constitutional Court where it had sought to overturn the appointment of Professor Firoz Cachalia as acting police minister. The apex court dismissed the challenge, upholding the President’s decision.

Not deterred by the legal setback, the party has since requested that the upcoming vote on the motion be conducted via secret ballot. The rationale, according to MK Party parliamentary leader John Hlophe, is to ensure MPs can vote independently and without pressure from party hierarchies.

In a formal letter to Speaker Didiza dated July 24, Hlophe wrote,

“This is particularly important given the sensitive nature of the motion and the potential political consequence for individual members.”

He further cited precedent set by the Constitutional Court on this matter, stating:

“A secret ballot will safeguard the integrity of the voting process and ensure that the outcome reflects the true will of the Members of Parliament.”

Although Parliament is scheduled to go into its constituency period from 22 September to 5 October, the MK Party appears resolute in its pursuit of the motion. The question that remains is whether procedural clearance will come in time for a formal debate or whether the matter will be deferred into the next legislative term.

At the heart of this political manoeuvre lies a broader question about the effectiveness of executive oversight and the extent to which political parties can hold the sitting President to account through democratic mechanisms. The call for a secret ballot only underscores the charged nature of this motion and its potential ramifications for South Africa’s political landscape.

Whether the Speaker grants the secret ballot or whether the motion even reaches the floor for debate in this term, the MK Party’s strategy has already ignited discussion within Parliament and among the public about leadership, accountability, and the power of dissenting voices within a constitutional democracy.